Saadia Toor, The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan. London and New York: Pluto Press, 2011.

Jadaliyya: What made you write this book?

Saadia Toor: I felt compelled to write this book because of the increasingly disturbing discourse on Pakistan in the West, both within the media and within academia. There is a mixture of incomprehension and hawkishness in this discourse when it comes to Pakistan, which is extremely dangerous given the increasing extension of the US/NATO war in Afghanistan into Pakistan. I believe that the ease with which even anti-war liberals (and sometimes Leftists) support, explicitly or implicitly, the covert war in Pakistan has to do with the fact that Pakistan has been constructed within media and academic circles in the West as a place overrun by extremists, as a place without culture (unless we are talking about raves or fashion shows being organized by the youth belonging to the elite classes) and, crucially, as a place without a history of popular struggle. The fact that it becomes very easy to bomb such a place is being borne out by the intensification of drone attacks under the Obama administration and the tacit or open support for them among liberal hawks both in the West and in Pakistan.

I wanted to subvert this discourse by highlighting the complexity of Pakistan’s history and the primacy of people’s struggles within it, as well as the role of the US-aligned establishment (and, at key junctures, liberals) in quashing these struggles and the alternate political and cultural visions they embodied.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does it address?

ST: The book analyzes key moments in the history of Pakistan through the cultural politics that defined them. The idea was to show the intimate connection between matters cultural and matters political, and specifically to point out how they have both been inflected by the Cold War and its aftermath. For example, in one chapter I analyze the exchange of polemics between members of the Leftist Progressive Writers Association and their liberal anti-communist detractors in the immediate aftermath of Independence. In another, I examine the contentious national debate that raged over the issue of the national language during roughly the same period, drawing upon newspaper accounts, Constituent Assembly debates, and reports of Government agencies. In a later chapter, I show how feminist poetry articulated a challenge to the regime of General Zia ul-Haq in the 1980s.

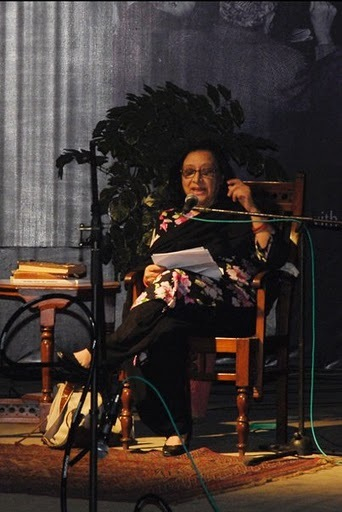

[Fehmida Riaz reciting her poem "Palwashe Muskura..." dedicated to Palwasha Bangash,

daughter of the late Mazdoor Kissan Party leader Afzal Bangash. Photo by Aliya Nasir.]

J: How does this work connect to and/or depart from your previous research and writing?

ST: If there is an overarching theme in all my work it is the connection between culture and politics, both in terms of the consolidation of power and resistance to it.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

ST: Given the fact that Pakistan is becoming an increasingly important front in the “War on Terror,” I hope that a broad spectrum of people, especially progressives, will read this book, both within and outside Pakistan. I would like this book to challenge, and hopefully contribute towards changing, the way Pakistan is understood in the West. I’d also like for it to have an impact on how Pakistanis understand their own history.

J: What made you decide to use the framework of the Cold War, and more recently the War on Terror, as a way to write about cultural politics in Pakistan?

ST: To me, this was simply the most logical way to understand cultural politics in Pakistan. The Cold War played an incredibly significant role in determining the trajectory of domestic politics in Pakistan—this is not news to anyone familiar with Pakistani history. However, to the extent that people in the West do make this Cold War connection, they tend to do it with regard to the Afghan War of the 1980s. I wanted to remind people that the relationship between the Pakistani ruling establishment and the US, which was born of and sustained by the Cold War, went back to the very beginning of Pakistan’s history as a newly-independent postcolonial nation-state and influenced its political trajectory in crucial ways. I felt that it was important to highlight the link between this relationship and cultural politics within Pakistan for several reasons. First, because I felt that it was important to talk about culture in the Pakistani context, since part of what makes the discourse on Pakistan in the West so problematic is that it is seen as a place without culture, and hence, a barbaric place. Secondly, culture and politics are intimately connected, and nowhere has this been more obvious than during the Cold War. In fact, there is now a very rich scholarship on the Cultural Cold War, and on the cultural organizations and initiatives such as the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the influential magazine Encounter, which the CIA created or supported as part of a cultural front against the Soviet Union and international communism.

However, this scholarship tends to be overwhelmingly focused on Europe and the United States. I wanted to show how important the Cultural Cold War was in postcolonial countries—especially postcolonial Muslim countries—such as Pakistan. The US saw newly-independent Muslim countries as crucial battlegrounds in the Cold War, because it believed political Islam—especially its conservative and reactionary forms—could be deployed as a Cold War asset, a potent weapon to neutralize the popularity of international communism in the poor nations of the world.

The Pakistani ruling establishment was itself invested in neutralizing the demands for social and economic justice made by ordinary Pakistanis. The relationship between the Pakistani establishment and the US—based on these shared vested interests—manifested itself explicitly within the cultural realm in Pakistan in the form of increasing state repression of Leftist writers, poets, and artists, and the elevation of right-wing, pro-establishment ones.

[Akeela Naz, a leading member of the Anjuman-i Mazareen-i Punjab, the landless peasants’ movement

that has taken on the army in various districts of the Punjab province. Image provided by the author.]

The Cultural Cold War in Europe and North America was led by anti-communist liberals. The same was true in Pakistan, and I wanted to show the effects that this liberal anti-communism had on politics, society, and culture. My main contention in this book is that the rise of a reactionary Islamic politics in Pakistan is directly connected to the repression, marginalization, and ultimate decimation of the Left as a political and cultural force, a project in which anti-communist liberals played a major role. I felt that this was a crucial intervention to make today when the same kinds of liberals—who tend to be hawkish when it comes to the US-led war in Afghanistan and Pakistan—are being held up in the West as the bearers of progressive values in Pakistan.

Excerpt from The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan

This tendency of the Pakistani establishment to turn to Islam—and, more importantly, to Islamist forces—in order to undermine progressive politics was evident from the very beginning and created the conditions for the increasing power of the religious right within Pakistani society and politics. Even then, this increase in influence did not proceed in any kind of neat fashion; this is a story of contingencies, contradictions, breaks and spikes. The Ayub regime, for example, went from actively targeting the Jama’at-i Islami to making strategic alliances with it when faced with mass mobilization on the Left. The secular and “socialist” Bhutto contributed to this trend (and set the stage for General Zia ul Haq’s efforts to Islamize Pakistan) by reaching out to the Gulf Arab states for moral and material support, and by choosing to appease the increasingly belligerent religious groups rather than strengthen his working class base. And it’s worth noting that even Zia ul Haq, a US-backed military dictator, the head of the most brutal regime in Pakistani history, met significant resistance when he tried to operationalize his Islamization project.

The institutional power behind specific ideological projects is far more significant than the inherent persuasiveness of the ideas they embody. The greater a group (or class’s) institutional power, the greater its ability to spread its own message far and wide and to suppress or misrepresent alternatives. Thus, we must look to such things as the balance of power between the different social forces, the confluence of domestic and international political agendas, and the political interests embedded in the various ideological projects in order to understand why a particular set of ideas—of the nation, the state, and (crucially) Islam—seems to “win” over others at any given moment in time. In Pakistan, as in other parts of the Muslim world, the rise of Islamists as a social and political force was engineered both directly, by inducting them into state institutions as Zia did, and indirectly by “cleansing” the political sphere of their only effective nemesis/counter, the Left. The story of the marginalization/decimation of the Left is thus a crucial part of the story of the Islamization of Pakistan.

Both the anticommunism of the establishment and the turn towards Islam as a means to undermine the Left had an international dimension. During the Cold War, the US establishment believed that Islam, particularly its radical variant, could provide an effective politico-ideological bulwark against communism in Muslim countries generally, and be a thorn in the side of radical nationalist regimes in the Arab-Muslim world. Saudi Arabia’s crucial function in this scheme was as an exporter of a rabidly anti-communist Islamist ideology. These Cold War scenarios were playing themselves out across the Muslim world, and were not unique to Pakistan. What really set Pakistan apart, however, and decisively changed the game, was the US’s proxy war in Afghanistan. It was through this war that violence in the name of Islam became legitimized, the means by which to inflict it became freely available, and the networks through which it was to be operationalized were created.

The book highlights the fact that “Islam” is far from a monolith, even within the specific context of Pakistan. It has always been and continues to be not only invested with different meanings and associations by different actors, but also articulated with wildly different political projects, and is thereby itself a deeply contested ideological field. This book illustrates the diversity of meanings and political programs associated with “Islam” through Pakistani history—from the modernist Islam of the Muslim nationalists, to the Sunni radicalism of the Jama’at-i Islami to the “Islamic socialism” of Bhutto’s People’s Party. This diversity, along with the popular heterodox forms of Islam indigenous to Pakistan, has been steadily under attack by domestic and international forces invested in a much narrower and far more intolerant version of the “faith.” The book offers an account of this contestation, and draws attention to the growing forces of radicalization and their relationship with the imperialist project, first under the sign of the Cold War and now under the Global War on Terror.

The other goal of this book is to resurrect the important role played by the Pakistani Left from the very inception of the nation-state in challenging both the Establishment and the religious right. While it is usually either ignored or dismissed as irrelevant within the mainstream discourse on Pakistan, the Left’s influence on Pakistan’s culture and politics has been significant and often far greater than its organizational strength would warrant. Many, if not most, of Pakistan’s most well-respected writers, poets, intellectuals, and journalists in the early period of its history were affiliated either with the Communist Party or the Left-wing Progressive Writers Association, or with both. The fact that they were and continue to be household names bears further testimony to their importance within the cultural and political life of the new state. The most obvious example is that of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, General Secretary of the All Pakistan Trade Union Federation, editor-in-Chief of Progressive Papers, Ltd. (a family of Left-wing periodicals), winner of the Lenin Peace Prize, and Pakistan’s unofficial poet laureate.

[The poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz—socialist, trade unionist, journalist, and Pakistan’s

unofficial poet laureate. Image provided by the author.]

While the Pakistani Left has been (often justly) criticized for the strategic errors which it made at various points, these mistakes must not be used to dismiss its contributions, for no other political formation embodied its progressive ideals of anti-imperialism, international solidarity, and social justice, a fact that becomes distressingly clear when we look at what has come to pass for “progressive” politics in Pakistan after the decimation of the Left in the 1980s. From the very beginning, members of the Pakistani Left faced hostility, harassment, and violence at the hands of the state. Faiz himself was incarcerated several times, but never left Pakistan until Zia ul Haq’s regime. Within Pakistan, the absence of the Left from mainstream accounts of Pakistani history is part of a concerted and ongoing attempt at limiting the political imaginary of the Pakistani people. Outside of Pakistan, these “sanitized” accounts reinforce existing stereotypes about Pakistan and Pakistani society as hopelessly reactionary.

This book is a small attempt to disrupt the mainstream account of Pakistani history by offering an alternative narrative, one which explains Pakistan’s present reality not as an inexorable unfolding of a teleology, but as the result of a complex and contingent historical process with both domestic and international dimensions. It aims to highlight resistance and struggle, and to document the important and historical role played by the Pakistani left in the culture and politics of the country.

...

The political economy within which reconfigurations of class and nation took place in Pakistan were clearly reflected in the new alignments within the literary-cultural sphere as well. Intellectuals and writers such as M. D. Taseer (a part of the original Oxford group that started the PWA), Samad Shaheen, Mumtaz Shireen, and Hameed Akhtar Raipuri—all members of the PWA and therefore part of the progressive consensus of the anticolonial period—abandoned the Association within the new political context with some going on to becoming its most articulate and die-hard liberal critics. The focus here on the liberal front against communism in this period is important for a couple of reasons. First, while there was an anti-communism espoused by the religious right as well, the Islamists were not yet a significant political and social force within civil society in Pakistan at this time. Second, the affinity of this liberal front with the international liberal front against communism in the cultural Cold War during this period was neither coincidental nor, as we shall see, irrelevant to the trajectory of Pakistani politics.[1]

Many of the members of this liberal front such as Muhammad Hassan Askari,[2] Samad Shaheen and Mumtaz Shireen were muhajir[3] and had a lot invested in the idea of Pakistan both emotionally and materially,[4] and so took their role in nation-building very seriously. As Intizar Hussain, a young writer at the time and part of Askari’s circle, notes in his autobiography, Partition changed Askari fundamentally from a proponent of “art for art’s sake” to someone who devoted his considerable energies and talents to the task of nation-building, putting forth the need for identifying and constructing a uniquely Pakistani literature, a demand which later came to constitute a major node in the ideological battle with the Progressive writers.

Despite the fact that the liberal anti-communist intellectuals continued to subscribe to many of the key values of “progressivism,” the stand-off between them and the Progressives was fundamentally antagonistic in nature. The latter were vocal carriers of a hegemonic socialist and anti-imperialist tradition within the Urdu literary community which dominated the intellectual space within West Pakistan. The liberal writers thought of themselves, first and foremost, as patriots who were committed to putting their considerable energies and talents in the service of their new nation-state. Crucially, they defined this project of nation-building as being incompatible with the socialism and anti-imperialism of the Progressives, and strongly identified the nation with the state, and both with the Muslim League government. Not only were they reluctant to criticize the Muslim League despite its increasingly authoritarian character, but they swore loyalty to it, demanding that others do the same or risk being labeled Fifth columnists. It is in these moments that the relationship between their politics and the interests of the ruling Establishment overlapped most neatly. Whether or not we understand this as a conscious complicity with the Establishment,[5] what is clear is that their anti-communist zeal served the purposes of the state, essentially turning them into organic intellectuals of the Pakistani ruling class.[6]

The Establishment and its organic intellectuals set out to accomplish the task of marginalizing the Progressives by seeking to discredit their communist/socialist vision with the help of Cold War propaganda. In addition, the fact that the Communist Party of India (CPI), with which the PWA had been affiliated, had withdrawn its initial support for the Pakistan movement just before Independence, was used to label the Progressives as enemies of the Pakistani nation-state. The consolidation of the ideological front was backed up by the coercive power of the state which was increasingly directed against Progressive publications and members of the PWA. Meetings of the Association were regularly disrupted, their publications proscribed, and several of their members jailed. The climax of these repressive measures came with the arrest and trial of Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Sajjad Zaheer in the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case in 1951 along with some senior and junior officers of the Pakistan army,[7] who were charged with conspiring to overthrow the government. The multi-pronged assault on the PWA helped prepare the ground for the ultimate banning of the Communist Party of Pakistan and its various fronts in 1954, just in time for Pakistan to cement its Cold War alliance with the US through the signing of the Mutual Defence and Assistance Pact.

...

In The Future of Culture in Pakistan, Taseer issued a call for war against two forces which he saw as attacking Pakistan from within: communists and religious obscurantists:

We welcome Pakistan because it has granted us our selfhood [khudi].[8] All those forces which are against Pakistan are our enemies, are the enemies of our art. We will battle these enemies, and reactionary forces which wish to strangle our freedom and independence, with whatever effective weapons we have at our disposal. We will fight this battle not just with sloganeering and proclamations but with our creative weapons.

The Progressives responded by denouncing the “so-called ‘Pakistani writers’” for spreading “the most vile and poisonous sort of nationalism” in order to “exploit the patriotism of the Pakistani workers for the selfish politics of the ruling class” (quoted from the APPWA Manifesto, 1949). Instead of facing up to the challenges posed by the realities of the post-Independence period, these nationalist intellectuals, charged the Manifesto, ignored the “real Pakistan which lay gasping on the ground; a Pakistan where there was poverty and unemployment, and Life was reducing to crawling on its hands and knees while an open season was declared for Death.” Instead of focusing on the plight of the people, they constructed “a bright and majestic Pakistan” through their “word-smithery” as a way to distract attention away from the true picture. When they

raise the slogan of “Pakistani literature” they do not mean that literature which refers to the desires and troubles of 95% of Pakistan’s people—they actually mean that literature in which the so-called “national services” of the ruling class are extolled, i.e., their oppression and tyranny is veiled…When these writers of a fascist mentality claim to be loyal to Pakistan, they mean loyalty to Pakistan’s capitalists, landlords, nawabs and other anti-democratic elements, not loyalty to Pakistan’s workers and their struggle. (APPWA Manifesto, 1949)

Zaheer Babar pointed out how odd it was that Independence should have been accompanied by a radical shift in the priorities of intellectuals such that writing about “peasants and workers” was now considered “boring” or even contradictory to the interests of “Pakistan” and “Islam.” No-one aside from the Progressives—least of all the “Pakistani writers”—bothered to ask to what extent Independence had changed the lives of these workers and peasants in whose name and on whose behalf it had purportedly been demanded. If anything,

[t]he people are still eagerly awaiting that freedom which will brighten their huts, that will give them their rightful return for their labor, which will release them from the exploitation of a handful of feudal landlords. We are not opposed to illuminated palaces, but the problem is that in our society every palace is surrounded by a great number of hovels which are at best lit by clay lamps…Pakistan would not exist without these people…it is because of them that the fields are lush and there is activity in the factories. It was for their cultural development and social welfare that a separate country was demanded. Pakistan loses its meaning if dissociated from these seven crore[9] people.

While the Progressives always couched their arguments within a discourse of patriotism, a fact which is easily established by a glance at their published statements, there was a key difference between their patriotic discourse and that of the “nationalist” intelligentsia. The Progressives tended to speak in terms of awam (“the people”) while the nationalists preferred the term qaum (“nation”). The choice between these two terms was not a semantic one. It represented a world of difference between two political philosophies and two incommensurable sets of interests. As Zaheer Kashmiri put it in his critique of the call for a new “Pakistani” literature, “for Samad Shaheen the biggest reality is Pakistan but for the Progressive Writers the biggest reality are the Pakistani people.”[10]

For the Progressives, the central issue was this: what was “the nation” in whose name loyalty was being demanded and whose interests the state purportedly served. Were religious minorities, Bengalis and the working classes part of this “national community?” The charge of “disloyalty” could thus cut both ways, depending on to whom “loyalty” was understood to be owed. To the “95% of Pakistanis” or the “ruling class which exploits them?” To “Pakistan” or “the Pakistani people?”

....

The hegemony of the socialist vision of the Progressive Writers in the literary milieu of the late 1940s made it imperative for the Pakistani state to discredit and marginalize them and their vision of the nation-state. Respected liberal intellectuals and writers such as M.D. Taseer and M.H. Askari consciously aided and abetted this state project.[11] It is a testament to the tenacity and the influence of the Progressive intelligentsia in Pakistan that it took the Government seven years to ban the PWA and the Communist Party of Pakistan. However, even that did not sterilize the public sphere of communist and socialist ideas, thereby requiring the actual take-over of the Progressive Papers Ltd.—a group of leftist newpapers and periodicals run by Mian Iftikharuddin and an outlet for the voice of the Progressives—in 1959 by the martial law regime of General Ayub Khan on the advice of another liberal intellectual, Altaf Gauhar. Along the way, many Progressives, communist and noncommunist alike, were jailed and some even lost their lives, but no amount of state repression or ideological assaults from the Right could completely stem the tide of dissidence in Pakistan, nor erase the hegemony of the Progressives within literary and cultural circles, as later chapters will testify.

“The nation” as a concept and idea is usually imagined as a community which exists above class and other petty divisions and is thus invoked in order to suppress the class question; in fact, however, it need not necessarily represent such reactionary interests. That it has generally done so points to the class character of nation-states in the modern period and the vested interests of those who, within them, have the power to define, delineate and police the boundaries of the licit and normative, including those of the “national.”

The Progressives and their liberal detractors were working with two entirely different and ultimately incommensurate definitions of “the nation,” and hence represented political projects which were diametrically opposed to one another. The anti-Progressive discourse of the Establishment and its organic intellectuals—the liberals—was nothing less than an attempt to impose a particular conservative vision of both the Pakistani nation and the ideal Pakistani state in place of the radical nationalism proposed by the Left. By discrediting the Progressives, these liberal intellectuals attempted to exclude the social, cultural, political and economic alternatives represented by this radical nationalism from the imaginary of the Pakistani people.

Ultimately, the harangues of the liberal anti-communists and their efforts to paint the Progressives as traitors proved successful insofar as they helped prepare the ground for the state’s repressive machinery to step in and resolve the “communist question.” The constituency which the anti-communist liberals were seeking to convince in order to enable the marginalization of a once-popular and now dangerous social vision was not the conservatives and religious reactionaries, but the majority of the Urdu literary and intellectual community, whose “structure of feeling” was still defined by the “progressivism” of the pre-Independence period.

The apparently paradoxical case of liberals serving authoritarian ends was hardly unique to Pakistan, being evident in the fascist tendencies and politics of many purportedly liberal writers of the early twentieth century. The cultural Cold War was in fact founded on a liberal anti-communist consensus, and led to the witch-hunts of the McCarthy era. Pakistan was already becoming a key American ally by the early 1950s and by 1953 the US had been invited to intervene in Pakistan’s political scene by the ruling clique at the Centre. In April 1954, Pakistan signed the Mutual Defence and Assistance Pact with the US, the first of many such formal alliances. A Pakistani branch of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the organizational forum of this liberal anticommunism backed by the CIA, was also in operation by the 1950s.[12] A new chapter in Pakistan’s history was about to commence.

Notes

[1] For details of the consolidation of this international liberal anti-communist intellectual front, see, inter alia, Saunders and Scott-Smith & Krabbendam.

[2] Askari was the only member of this camp who had not had a relationship with the PWA before Partition.

[3] The word came to be used to refer to those who migrated from India to Pakistan. In time, it became associated with those who hailed from North India and Hyderbad more specifically.

[4] Serious work needs to be done on analyzing the extent to which the loyalty that liberal, modernist Muslims felt towards the Muslim League was mediated through the personality and charisma of Jinnah, insofar as he represented the quintessential modern Muslim leader—Western educated and yet committed to the welfare of his community.

[5] Taseer and Samad Shaheen were high-level civil servants in a country ruled by the bureaucracy, but Askari had no such direct connections.

[6] I use this term in the Gramscian sense of intellectuals who represent a particular class’ interests in the struggle for hegemony.

[7] One of these junior officers was Major Ishaq Muhammad, who would later establish the Pakistan Mazdoor Kissan Party in the late 1960s. Muhammad also wrote the introduction to Faiz’s collection of poetry Zindah-Nama (“Prison-Letters”) which the poet composed during his first term of incarceration.

[8] Literally, “the self.” “Khudi” was a concept popularized by Muhammad Iqbal who saw the awakening and strengthening of the Muslim (man)’s khudi as the prerequisite to the Muslims’ return to glory on the world stage. Taseer’s choice of words is thus entirely conscious—linking the establishment of Pakistan to Iqbal’s “dream” of Muslim glory—and the reference would have been instantly understood by his readership.

[9] One crore = 10 million.

[10] Savera, numbers 5/6, as quoted in Fateh Muhammad Malik.

[11] Intizar Hussain, an anti-Progressive liberal himself, admits in his memoirs that one of the reasons Askari did not begin writing earlier than he did (that is to say, a few months after Partition) was because of the hegemony of the Progressives: “This was the era of the zenith of the Progressive Writers Movement in the entire subcontinent. Even those who weren’t Progressives accepted guidance from them/were effected by them in some degree or form. If there was a dissident, he didn’t have the guts to voice opposition to them.”

[12] Sibte Hasan, a well-respected Leftist journalist and major figure in the Progressive Writers Association, actually argues that the PWA was banned “under American pressure.” Hasan also mentions that branches of a CIA-sponsored publishing house called Franklin Publications were opened in the three main urban and cultural centers of Karachi, Lahore and Dhaka. The publishing house also employed and contracted Pakistani writers to translate American books into Urdu, paying them handsomely for their services; these books were then distributed free of cost to local booksellers.

[Excerpted from Saadia Toor, The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan. © 2011 by Saadia Toor. Reprinted with the permission of Pluto Press and the author. For more information, or to purchase the book, click here or here.]